WORK PACKAGE 5: FINANCE AND WELL-BEING

Work Package 5 (WP5) on Finance and Well-being aims at evaluating the differentiated impact of financialisation and of the crisis on well-being in the EU, focusing in particular on the relations of households with the financial system. To pursue this goal it combined different types of quantitative and qualitative research methodologies in order to explore how citizens interact with the financial system and the impacts it has on their daily lives and longer-term outcomes. This article presents the results of a survey on finance and well-being carried out in five EU countries and that of a participatory research engaging marginalized groups in nine different European countries.

The latest Working Paper of WP5 (FESSUD Finance and Well-being Survey: Report, Working Paper Series No 130, January 2016) , presents the main results of The FESSUD Finance and Well-being Survey, which inquired about household engagement with finance and the impact of the financial crisis in five EU countries considered representative of different types of financial system and welfare regime: Germany, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

Reflecting the relative country positions, in terms of socioeconomic development and the maturity of the national financial sectors, as well as household diverse social standings, the survey provides plenty evidence of household differentiated engagements with finance across and within countries. Notwithstanding country differences, it also shows that financialisation involves predominantly the higher socioeconomic strata, who are most embroiled with finance via mortgage and financial asset markets, and in particularly beneficial ways.

Households with mortgages by income group (%)

For example, participation in mortgage markets has revealed to be not only a means of improving household living conditions, being associated with higher levels of reported satisfaction with accommodation, but also a means of accumulating wealth due to the spectacular valuation of residential property during the financialisation era, even if not uniformly, depending on temporal, spatial and social contingency. At the same time, housing has become less affordable to the lower strata and a growing mechanism of marginalisation of those excluded from mortgage markets and the private rental sector. This is consistent with other research within the FESSUD project that has exposed how the financialisation of the housing system of provision has pushed the excluded into the margins as financialisation dysfunctions produce new vulnerabilities (see, for example Robertson, 2014; Santos et al., 2015).

Satisfaction with accommodation by tenure status (scale 1-10)

These developments have occurred at a faster pace in countries with more mature financial systems and that have been at the forefront of transition from collective to more individualised forms of welfare in recent years, such as the UK and Sweden. But the impacts of financialisation on well-being cannot be simply read off from the sizes of national financial systems or the extent of household engagement with finance. Systemic trends and their manifestation at the national level produce varied and differentiated results, depending on how finance interacts with relevant systems of provision and broader welfare provisioning.

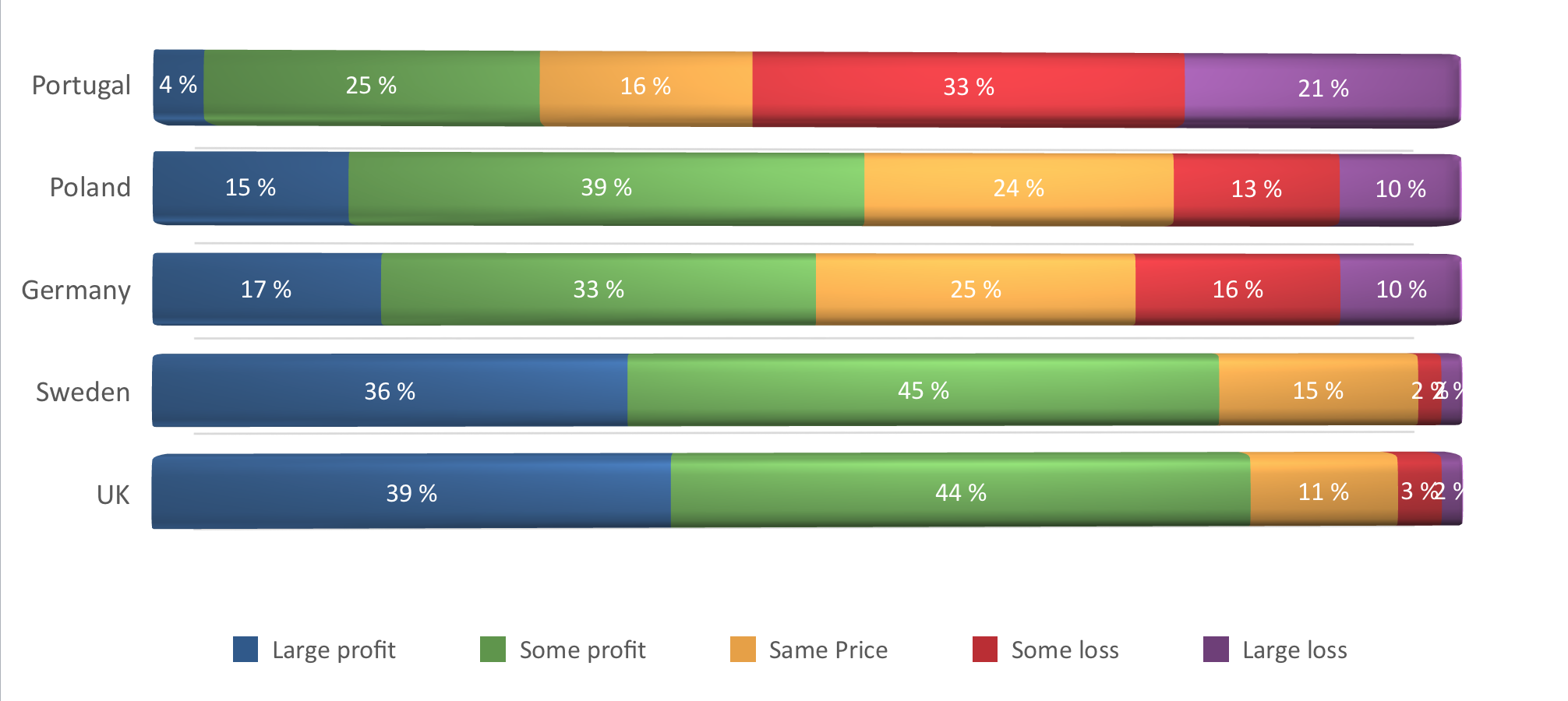

Potential profit or loss of selling household accommodation (%)

The countries most severely hit by the financial crisis were not the most financialised countries of the West and North of Europe where household dealings with finance are most widespread (e.g. the UK and Sweden). Nor were the least financialised countries from East Europe found to be most protected from these impacts (e.g. Poland). The most severely affected by the crisis were the Southern European countries with the more fragile and more financially integrated economies, as financialisation processes have rendered these economies more vulnerable to external shocks (e.g. Portugal). As the countries most negatively affected by financialisation and the financial crisis are also amongst those with the biggest gaps in their welfare systems, they have also endured the most severe social impacts.

The survey then lends support to the conclusion that the impact of financialisation and of the financial crisis on well-being depends on many interacting factors. It depends on overall levels of economic and financial development, affecting most the weakest yet financially integrated economies exposed to financial turmoil. It depends on the particular ways relevant systems of provision have become increasingly financialised and more prone to reproduction and consolidation of social inequalities. And it depends on recent transformations on broader welfare provision, especially the extent to which it has pushed the most vulnerable to the margins of a welfare model where provision has become more commodified.

As part of the research carried out in WP5, generally bearing on the relationship between financialisation and well-being, POUR LA SOLIDARITÉ – PLS, in partnership with 9 civil society organisations (CSOs) from different EU countries (Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Sweden and the UK) employed a participative methodology to elicit the views of marginalised groups on the financial sector. The objective of this research was to reimagine finance from the perspective of the marginalised. It specifically looked at: how would inclusion look like if it happened on the terms of the socially disadvantaged? What reforms do socially disadvantaged regard as crucial to either achieve inclusion on their terms or have an alternative financial system better serving their needs? How are socially disadvantaged involved in the financial system and which dimensions of well-being are touched upon?

The deliverable presenting the results of this research will be published on the FESSUD website in the next two months, however the preview of the main common themes featured by the reports can already be made available here. Based on workshops organised with different categories of marginalised groups – unemployed youth, people from migrant backgrounds, low income students, women at risk of poverty, small farmers, sex workers, dwellers of self-built neighbourhoods, the following themes have been highlighted in the 9 different national reports.

Participants spoke about very pronounced negative effects on emotional well-being due to financial exclusion: fear not to be able to pay back a loan, fear to fall prey to a scam, being treated disrespectfully, feeling not to be listened to and lack of understanding of personal situation, feeling exploited, constantly having to be on one’s guard as one cannot trust financial institutions one is forced to deal with, feeling excluded

- There is a shift “from welfare to debtfare”, a decisive structural feature of the current situation, which negatively impacts people’s well-being, due to the very structure of finance and the negative effects of dealing with it (stress in managing repayments, fear not to be able to stay on top of one’s debt, repossessions etc. shown by the national reports).

- There are two sides to the medal of negative effects on people’s emotional well-being: on the one hand, they seem logical given that people simply do not have enough financial resources to meet their needs, for which the financial system cannot directly be blamed; on the other hand, the research clearly shows that people do not trust the financial institutions that are supposed to rely on for advice and financial products or solutions. This in and of itself creates emotional stress (feeling alone, fear of being exploited, not being treated respectfully, not being heard, etc.) and leads to negative outcomes (falling prey of a scam out of desperation, not turning to financial institutions even if they could offer an appropriate service, etc.).

- Abandonment of citizens in need by both the state and the financial system – both the state and the financial system are not taking responsibility. This is best summed up by a statement from the Italian report: “They feel threatened by the bank, which still asks for payment, and abandoned by the State, which does not provide any kind of assistance.” The interplay between a state that is abandoning them and a finance system they do not want to or cannot turn to has occurred in all participating countries.

- The distrust of citizens in the finance system is justified, so the solution shall not be PR-driven trust enhancing initiatives but changes in the way financial institutions are governed, structured and regulated. This links to peoples’ wish for financial institutions they feel more in control of and which are trust-worthier, so that the negative effects on emotional well-being stemming from the engagement with banks are minimised. (Obviously, this is additional to the fact that there are negative effects from the mere fact of being poor, which cannot be addressed through bank reform, but would require different welfare policies, economic policies and so on.)

- People are forced to engage with the financial system, especially having a bank account; in order to get their benefits or income or pay basic bills. There is a sense that bank has guaranteed costumers, even if it treats them badly. This means a very serious power imbalance and a need for alternatives from the perspective of choice: because the culture of banks is experienced as pervasive, it seems inescapable: even if banks treat people badly, they have no alternative to go to.